A modern retelling of The Oval Portrait by Edgar Allen Poe

Photo by Zafer Erdoğan

Summer in the tropics, can you believe it?

There wasn’t a cloud in the sky when I put my Staffy-cross mutt Tyson in the car and drove out to Cooloola beach for a day out of the house we both desperately needed. It was his idea, really.

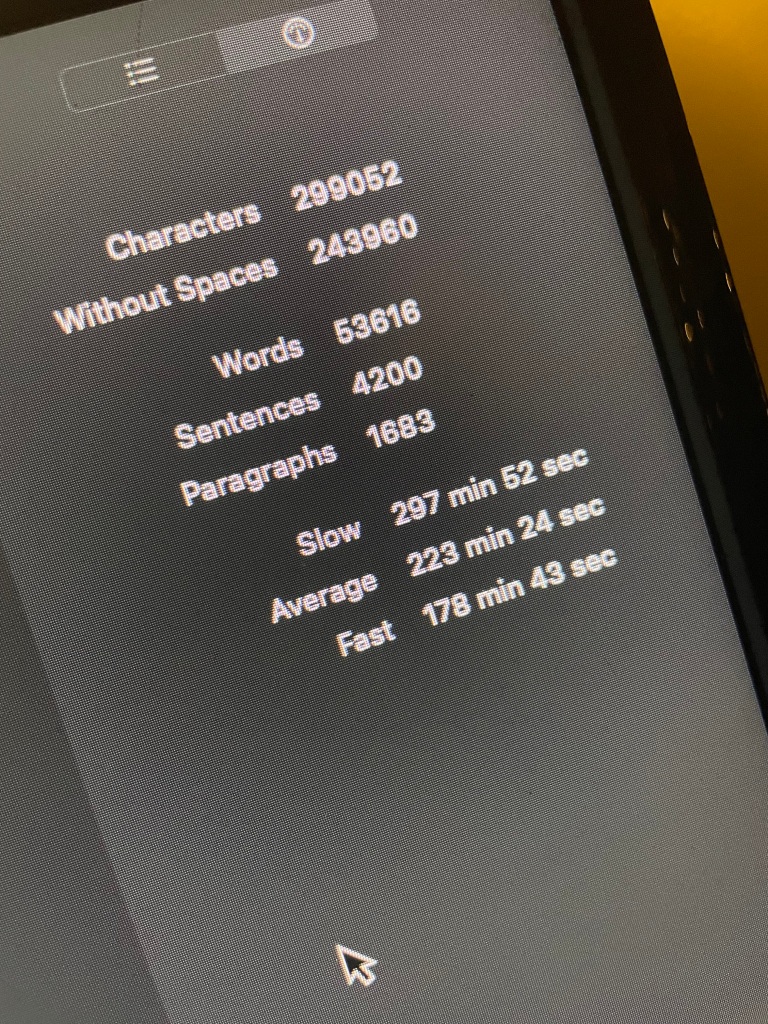

Things had been rough on him since my partner moved out, I had turned in on myself and — I’ll admit it — shut down a little. Groceries were delivered, I drank a bit too much, and I hadn’t written a word of my book in over a week. Show me a calendar, force me to tell you when I last took Tyson for a long walk, and you’d make me a liar. So, we both needed it.

The sun blessed our arrival but quickly turned its back on us when we had wandered a few kilometres from the car. A storm blew in from the north, raking Frasier Island and gathering steam over the Great Sandy Strait before it hit us. Being pelted by the thick hot droplets was bearable, but after the third rip of thunder caused Tyson to stream urine down his leg and fleck the sand in our wake, I knew we had to find some shelter.

Up the north end of the beach is usually quite deserted, so that was the way I had taken us, sending Tyson ahead with throws of a plastic frisbee, but the trees were sparse. Just beyond an eroding sand dune, a beautiful white house grew out from the grassy rise, its balcony jutting over the drifts and scrub to stand on thick supports.

We scrambled up the sandy hill as another lighting strike shredded the air and sucked the oxygen from my lungs. I grabbed Tyson and threw him over the glass divider of the balcony’s hand rail. As I got a foothold to hoist myself up, I noticed how sand-blasted and grimy the glass panes were.

“Shit,” I muttered to myself as I fell onto the weather-beaten boards and got to my feet, “if I had a place like this, I wouldn’t let it go to hell.”

My inner critic, sounding more and more like my ex-partner the longer I listened to it, said, “If you could finish your book, you useless piece of shit, you might afford a place like this.”

Either way, the sunrises from this balcony would be a hell of a sight. I put my back to the granite wall, sheltering as much as I could under the narrow eaves. Rain still whipped us, the wind tugging at my clothes, and Tyson was whining worse than ever.

“Bugger this,” I shouted, “come on, boy.”

I might not be able to afford a designer cottage on the beach, put together by some wank of an architect, but I can afford to pay for the repairs to this window.

It gave in after the second kick, and I wrapped my hand in the sleeve of my hoodie to pick the shards out of the frame, enough to undo the latch and slide it across. Tyson jumped in first, onto a marble kitchen bench, deaf to my warnings of broken glass. I followed, nearly twisting my ankle in the deep sink, and we collapsed inside. Tyson spelled out his gratitude with licks, until I stood and gathered myself.

For a summer home, it was obvious this place hadn’t been touched in two summers or more. Dust coated everything, its flakes ruffling under the sudden exhalation the storm was demanding through the broken window.

I checked my phone. No signal.

“I bet that last lightning strike took out the tower, hey, boy?” I asked.

Tyson laid one ear back, to express his uncertainty.

Activating the flashlight, I stepped deeper into the house. Every halloo came back with a flat and short echo, a clear sign there was nobody home, only us two intruders. Still, I couldn’t be sure the house lacked that flatline feel which lets you know you’re alone.

Most of the rooms appeared unfurnished, until I realised most of the rooms toward the back of the house — or the front, from the road and garden — had been converted into an art gallery.

Photos lined the walls of every empty room.

I’d never had the eye for photography, but I’d been dragged to a friend’s opening or two. Something I’d picked up was, the more posh the gallery, the smaller the art and the more widely spaced it is. This was high up there in terms of of grandeur, the floorboards still foggy with polish under the dust, and many of the photos not much larger than a dinner plate, three or four to a wall in most rooms.

They were alright, I suppose. I write historical fiction about knights stabbing each other. I’m no hipster.

On the cushion of one chair was a glossy booklet, about the dimensions and feel of a haute-couture magazine, so I picked it up and held it under my flashlight to read the title.

Galerie Manquante; 2021

“Two years old. What do you reckon?” I asked, and held the booklet out to Tyson. He sniffed it, unimpressed.

I took it with me as I inspected the other remaining rooms. Some had obvious gaps where photos had been hung but were since sold or removed, each one with a title and year under it, but no price. I flipped open the booklet and saw it was a guide to the gallery, each photo blessed with a backstory and a short essay of praise from some industry influencer.

Page two explained that the photo to my right, a landscape of the beach outside at sunset, had the symmetry and form of a flower, while its accompanying text compared the layout to that of a woman’s labia.

“Sheesh.”

I tucked the booklet into my back pocket and found a set of stairs leading up — if the kitchen and balcony were any indication, this was the home of the artist or the curator, or both. I shouted a final enquiry up the stairs and, receiving no reply, started up. Tyson was hesitant to join me and only came when I insisted and slapped encouragement onto my thigh. We had to dry off somewhere.

Lightning and thunder momentarily cracked the world open outside once again, and Tyson slipped past me at the stairs landing, beating me to the second story. I followed, phone light held aloft. The first door opened to a bedroom.

I guessed, during the last visit by whatever cleaning service the owners engaged with, the housekeeper had thrown a plastic protective sheet over the bed. This I tugged to the floor before climbing into the bed for a rest. We’d walked at least three kilometres before the boiling clouds had chased us into this house, and I was dog tired. Pardon the pun.

Tyson did not jump up with me, as he often tried to do at home, stubbornly put his back to the windows and flattened his ears. He’d never liked thunder.

Angling myself to read by the diffuse grey light from the windows was too much a strain on my eyes, so I propped myself up on the stale pillows and read by the flashlight of my phone.

Back on the first page, a local professor had written an introduction which sounded like it could belong in a eulogy, or an entrant for the worst-ever best man’s speech at a wedding.

“Sid and Nancy,” it read. “Kurt and Courtney. Bonnie and Clyde. Now, Jean and Patricia. How volatile a compound two lovers can be, when they are both creative and troubled. Though now estranged and separated, this artist and his muse were together for the most capricious and productive years of their lives. She wasn’t a model when she met him, but the guitarist of indie band The Modern Poets, and he was a travelling photographer.”

I skimmed ahead, flipping over a few pages and feeling the irregular shuffle of harmed pages tickle at my fingertips, when I saw a woman staring at me in surprise out of the corner of my eye.

I yelped, dropped both the guidebook and my phone, casting that corner of the room into shadow.

“Shit!” I shouted, heart slamming, “I’m sorry! I thought the house was empty!”

I scrabbled in the stiff downy covers for my phone, lighting only my other hand as I picked it up upside-down, and finally righted it to point at the corner again. My explanation about sheltering from the storm died on my lips when I saw what had given me a fright.

A portrait, like the dozens of others downstairs, was pinned to the far wall.

It had been snapped at the perfect distance to look like a woman had turned to look at me in the doorway leading to a walk-in closet or ensuite bathroom which was not there. She was pretty, blonde, tanned more on the shoulders and cheekbones than elsewhere. She’d been photographed seemingly without warning, turning around to see the camera go off at the precise moment the artist wanted to, mouth open enough to accentuate her lips, and shoulders turned to catch the sun.

It was the way the light reflected from the ocean hit her eyes that made them look real and alive.

A low moan floated through the house, but it was only the storm blowing through the kitchen’s broken window. I rubbed my eyes, grabbed up the guidebook, and kept reading. Summer storms don’t last long, we had to get comfortable and stay entertained. This guidebook would have to do, all there were on the walls in this bedroom were empty dressers and awards on shelves.

I thumbed through again, locating the first of the damaged pages. A whole quarter had been ripped out, but the accompanying editor’s note had this to say;

“Patricia was never more beautiful than when she was smiling. I always said Jean got married to his art before he left high school, so I told Patty, I told her, ‘Kid, your only rival will be his art.’ She smiled when I said that.”

Another few pages of landscapes and still-lives later, I came across another page with its accompanying photo ripped out. This, too, referenced the Patricia in the past tense. One caption called the couple “estranged”, and they had not seen each other in some time.

“They worked harder than any other creative team I knew, always in the search for the perfect light. No photo they took looked less than amazing,” said one.

“Jean has that perfect selective deafness a true artist needs, to block out the detractors and critics. I’ve been in digital imaging for twenty-five years, and I can promise you there’s no Photoshop or post-processing on any of these. Pat just photographed that well, even if she was getting wrinkles at twenty-nine, last I saw her, she’s just that photogenic and Jean’s just that good,” read another.

I turned another mangled page, then saw this was the page speaking of the portrait I saw pinned to the bedroom wall. It had the same caught-in-the-moment candidness of the version before me, but was far smaller and lacked the ultra-reality had given me a fright. This time, Jean himself had written the tagline.

“Artist’s note: Click, and it is perfectly done. Captured. This is life itself.”

Then, on the final page, a paragraph insisting all proceeds raised from the sale two years ago would go toward the search efforts for the missing Patricia.

I looked back up, lowering the guidebook and raising my phone. Tyson growled.

On the paper tacked to the wall, under the searching flashlight of my phone, her glittering eyes stared back at me. It really did feel like life had been captured in there.

The photo blinked.

End.